From Static Forms to Intelligent Systems: The Next Transformation in Court Access

Part 1: The Evolution of Court Information Systems

History: From Paper to Process

Courts are in the dispute adjudication business, but to adjudicate, they need accurate information from the litigating parties. Historically, that information arrived as free-form narratives written in legal language—pleadings, answers, and motions—that only trained professionals could navigate. For self-represented litigants, the task was daunting: what to include, how to phrase it, or even what the court expected.

Courts realized that this reliance on free-form pleadings made justice inaccessible to most people. The solution was standardized forms—documents that reduced the burden on litigants by clarifying what information was required and how to present it. These forms also made it easier for court staff to locate key details, such as names of parties, dates, claims, and requested relief.

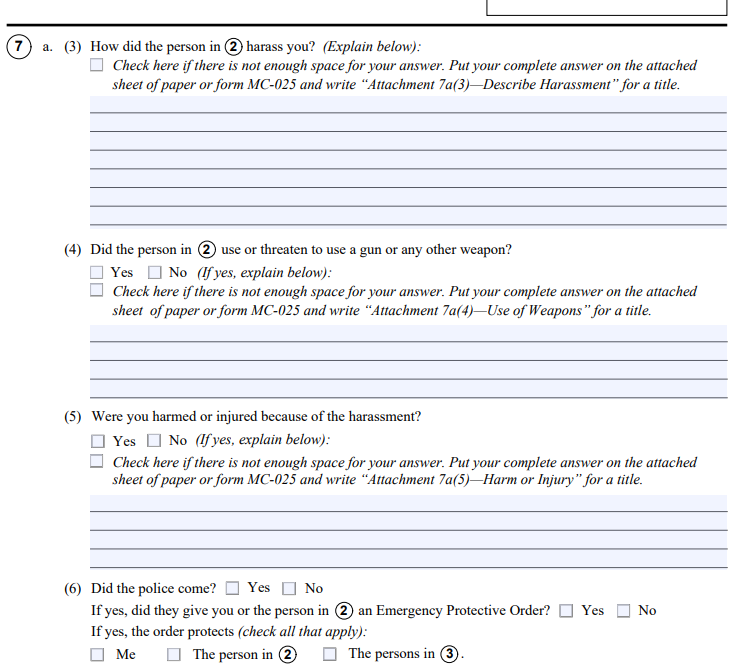

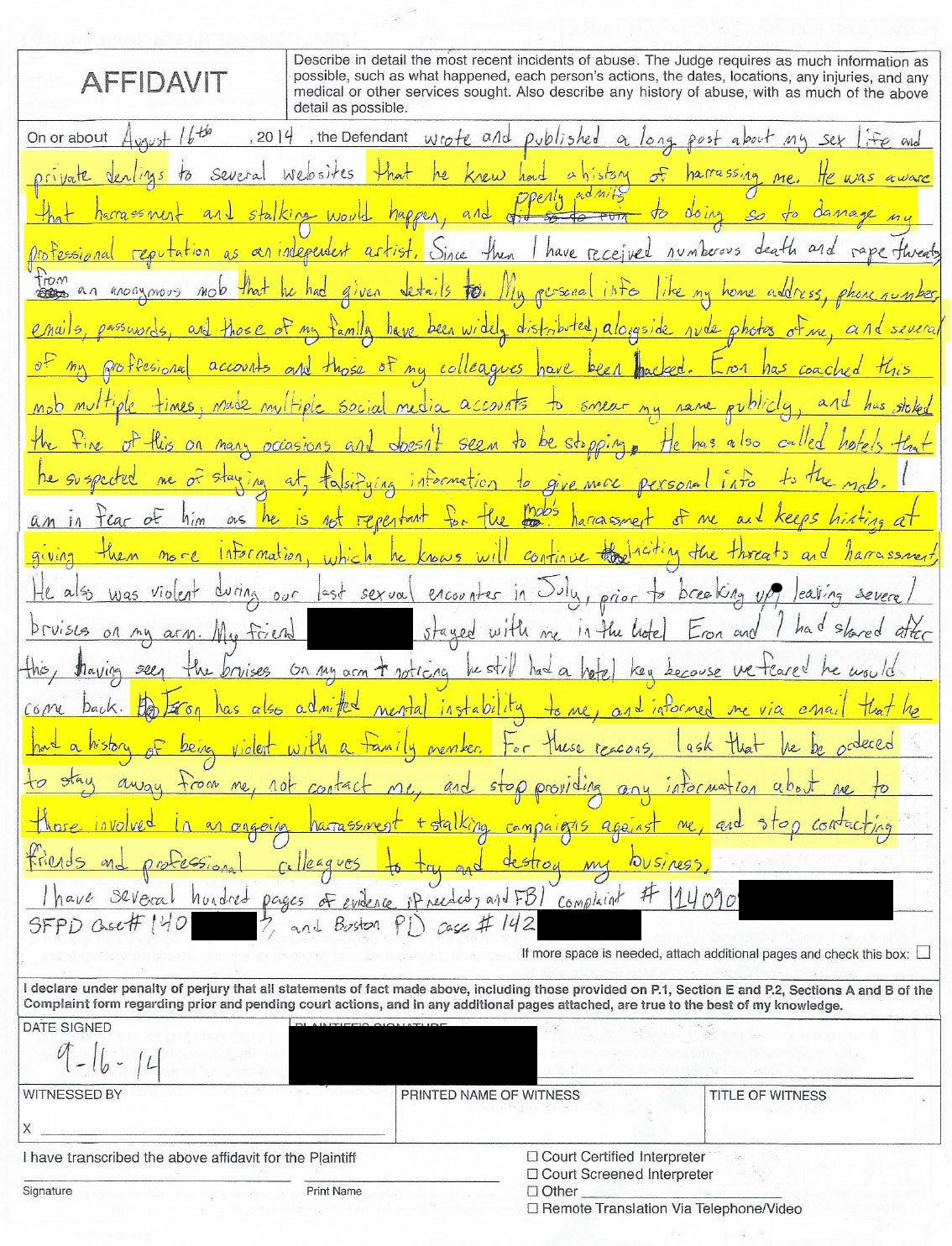

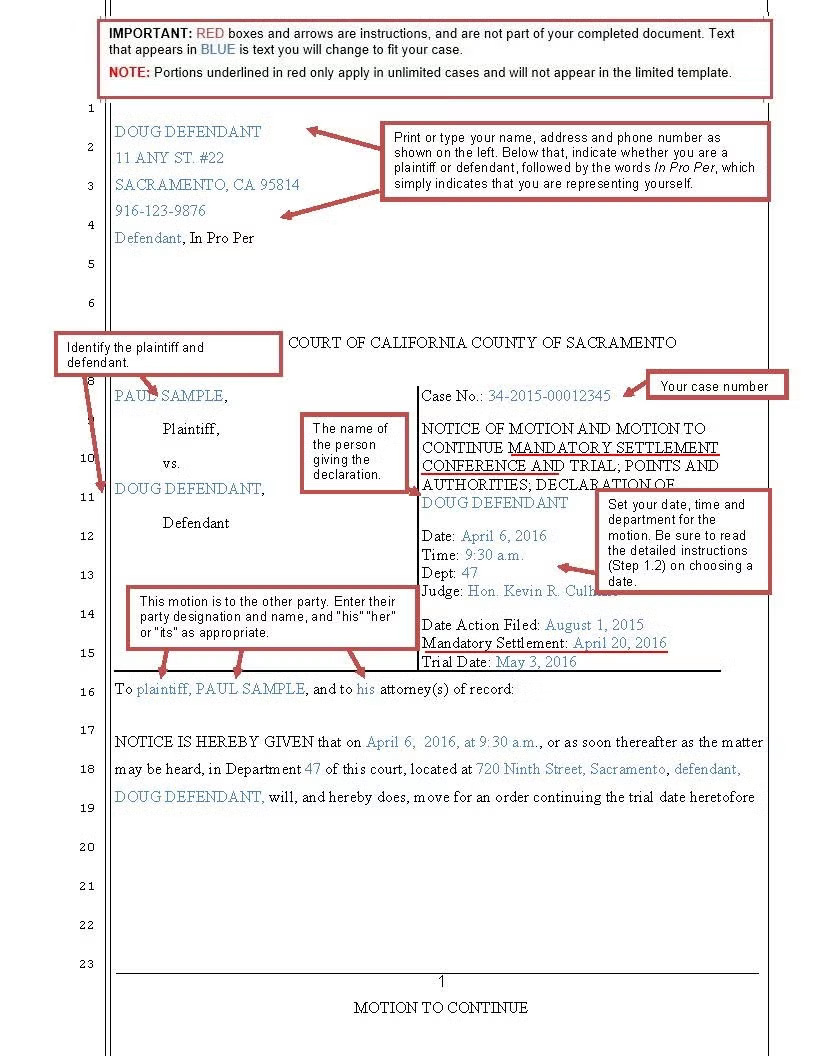

The images below illustrate this evolution. Figure 1 shows a traditional pleading, in which litigants were expected to compose their filings from scratch using technical formatting and language. Figure 2 shows a portion of a standardized California Judicial Council form that reveals, through its questions and structure, what the court considers important to deciding the case.

Figure 1

Figure 2

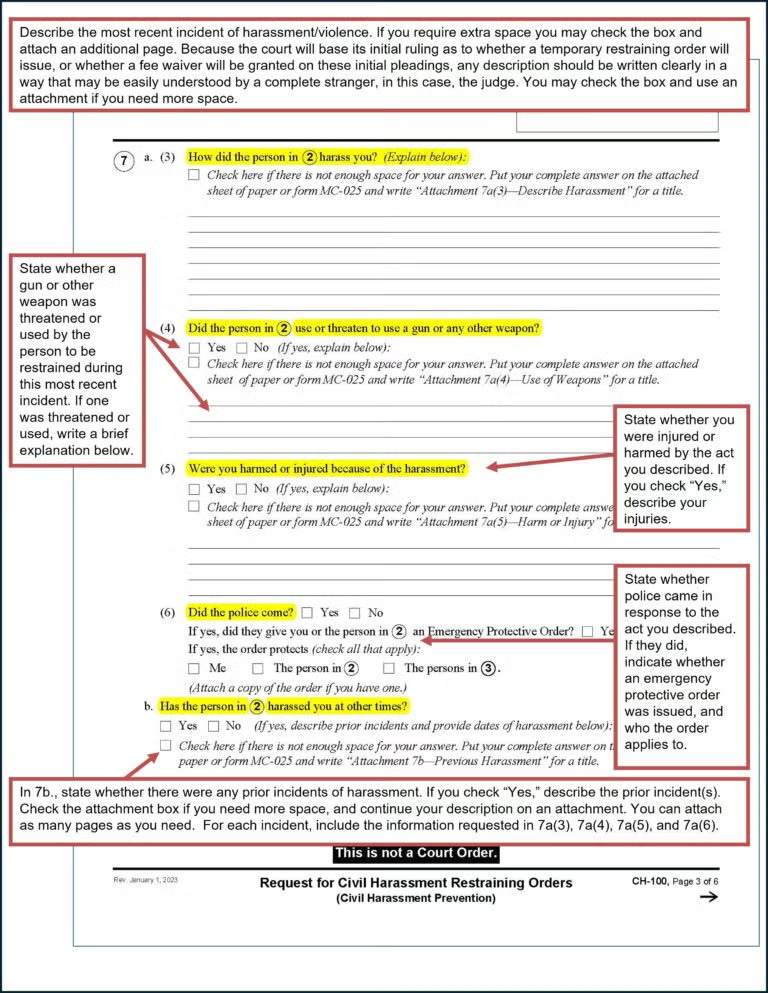

Still, forms were static tools. Many litigants continued to struggle, either providing incorrect information or simply leaving fields incomplete. Even well-designed forms, like California’s Request for Civil Harassment Restraining Orders, required significant additional instructions. Figure 3 was taken from the Sacramento Law Library’s self-help website for self-represented litigants. They added the red boxes to explain how to complete this form correctly. Even the supplemental instructions often require further clarification of legal terms and their use.

Figure 3

Guided Interviews: Solving the Problem of Static Forms

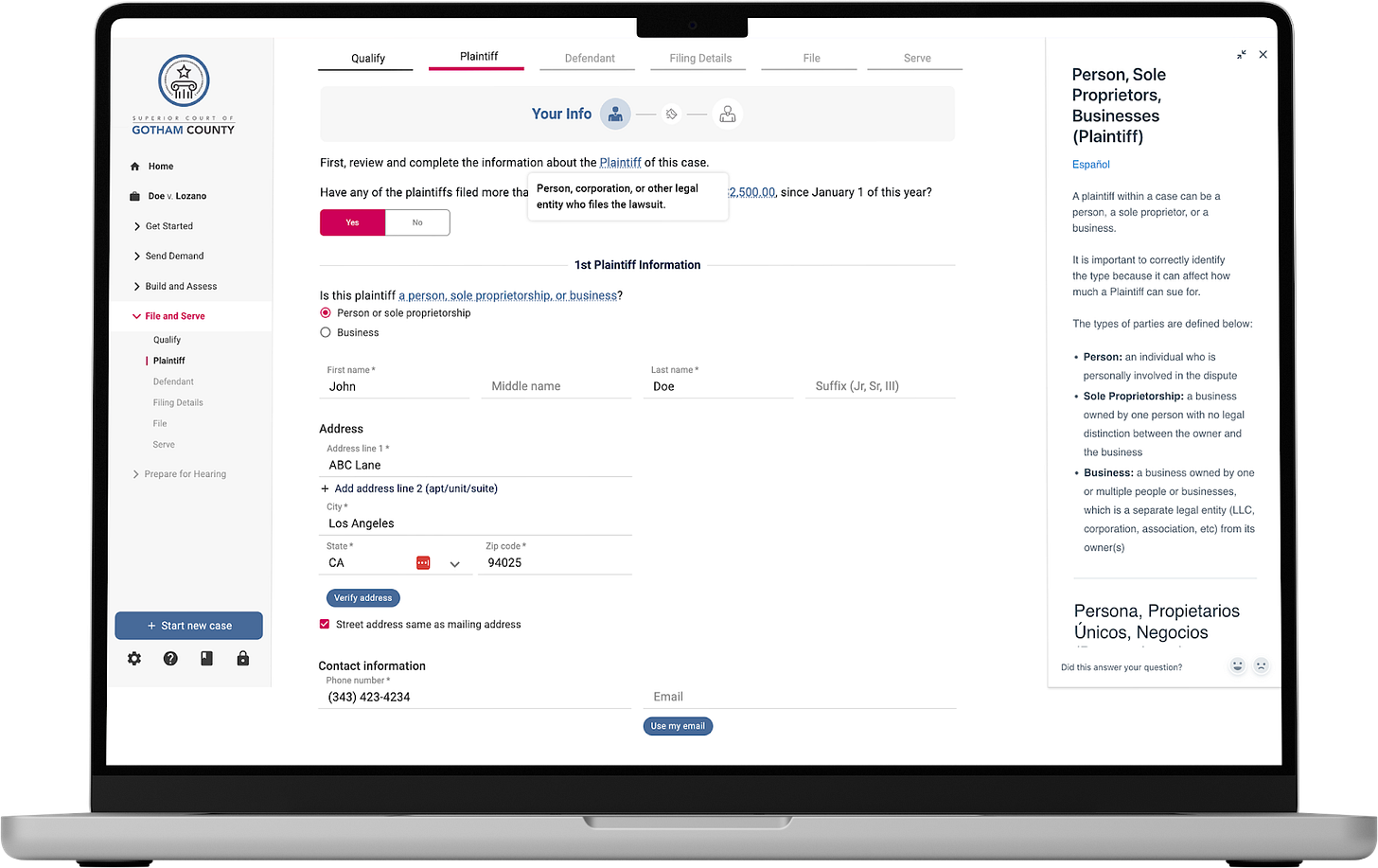

To solve the limitations of static forms, courts introduced guided interviews—digital interfaces that guide users step-by-step through the filing process. Figure 4 below is an example of a guided interview:

Figure 4

Unlike a blank form, a guided interview asks one question at a time, and provides explanations, examples, contextual help articles and validation checks. It ensures required fields are completed and it flags inconsistencies before submission. Some common errors are caught early, improving accuracy and reducing clerical corrections.

Guided interviews changed how litigants completed court forms. However, structured forms still don’t work for every court action. Sometimes litigants need to convey information to the court via open-ended narratives or detailed structured reasoning, rather than tightly constrained form fields.

The Challenge of Free-Form Information Remains

Certain documents—especially affidavits, motions, and other narrative filings—demand a level of reasoning or storytelling that forms and interviews cannot capture.

Affidavits

Affidavits recount events in personal detail, linking cause and effect through experience. But such narratives are often disorganized or incomplete. Litigants may omit key facts or bury them in emotion-filled paragraphs, making it difficult for judges to extract what matters. Under stress, coherence suffers, and both litigant and court lose efficiency.

Figure 5 illustrates that even when presented with a form, users may still handwrite their testimony.

Figure 5

If you read this affidavit, you will see that there are many claims. The judge would have to manually separate the claims and determine which ones litigants have provided evidence for, and which ones they have not. This process is extremely tedious, time-consuming, and fraught with error.

Where affidavits depend on personal narrative, motions demand logical structure.

Motions

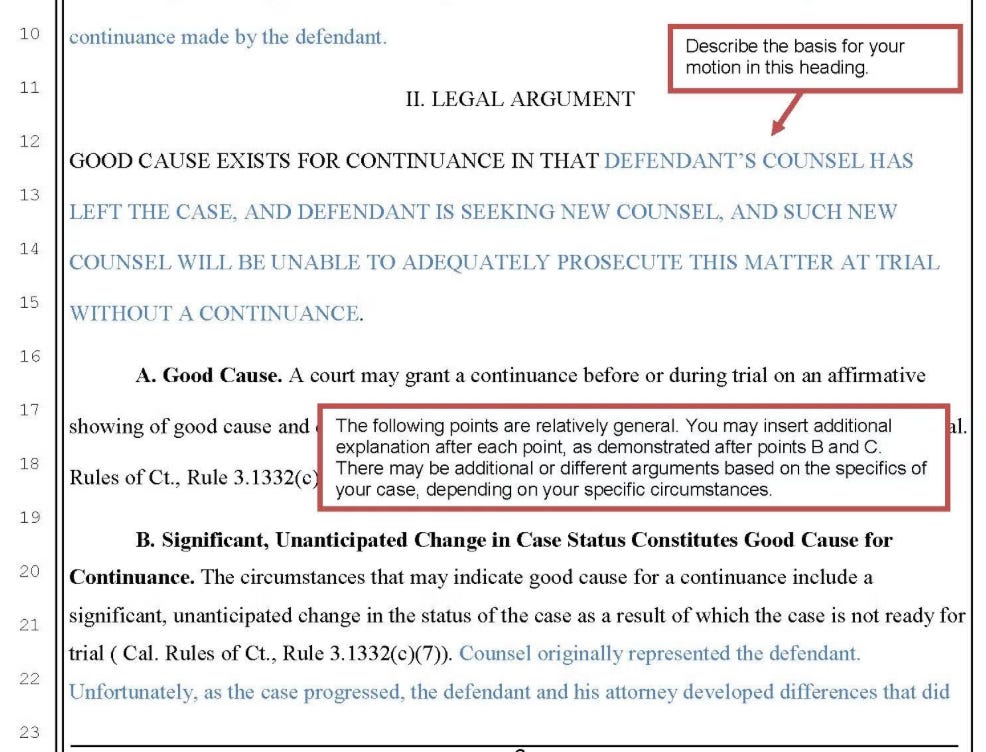

Motions, by contrast, require structured reasoning. They must identify an issue, cite applicable rules or case law, apply those rules to the facts, and conclude with a specific request. Self-represented litigants often struggle not because they lack facts, but because they lack the framework lawyers spend years learning to use.

Consider a litigant who needs to reschedule a hearing due to childcare conflicts. Her first challenge is knowing whether that qualifies as a legitimate reason; her second is formatting the request properly. Figure 6 is an example from the Law Library of an image of the header of a motion for continuance. The extensive mark-up on this document (instructing litigants on what information to provide) is evidence that motions are very difficult for a non-lawyer to create.

Figure 6

After the header, the litigant has to provide an argument showing good cause for the request (Figure 7):

Figure 7

A self-represented litigant is unlikely to know what “good cause” means, what arguments would satisfy that standard, or how to structure the argument in a legally sufficient way. Attorneys rely on templates and precedent to construct such arguments, while self-represented litigants must build from nothing.